You can benefit from the scholarship involved in Complete Composer Critical Editions by consulting a complete edition in Armacost Library (if we have it) or accessing a performing edition derived from the complete works edition.

How can you tell whether a performance score that you come across is based on rigorous scholarship?

Attributes of the score itself, such as the presence of an introductory essay, footnotes, or source citations at the end of the score, might help you understand the nature of your score.

Many scores are reprints of other publications, particularly for works not under copyright. Check for a statement at the front of a printed score indicating it was reprinted from another source.

If the origin of your score is still unclear, try researching the publisher.

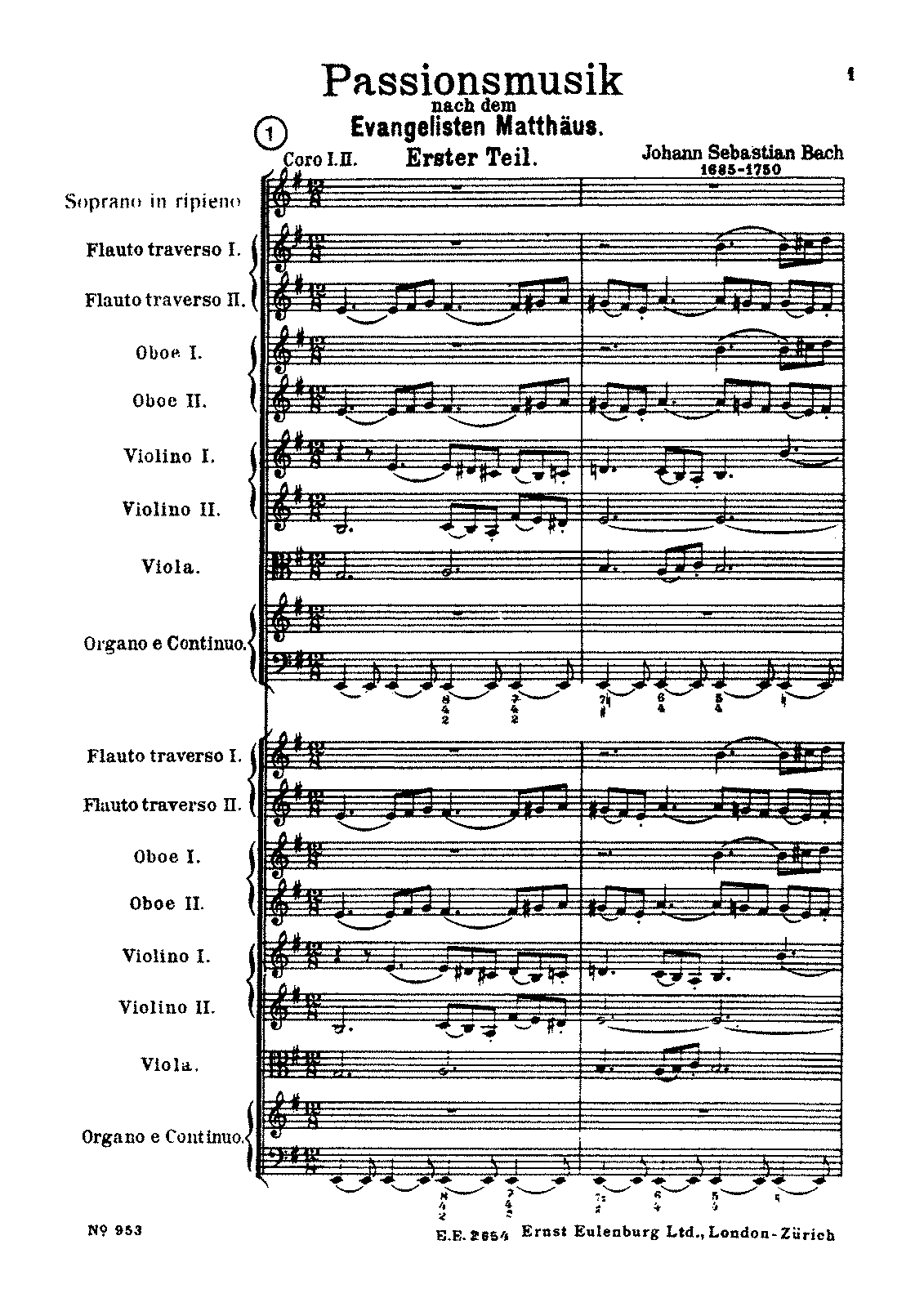

Here are some examples to practice on.

What can you determine about these scores based on information in the catalog record (for physical scores) or information in the website and on the score itself (for online scores)?